See if you can make the connections.

Patton [excerpts]:

Movement and supply [of mass armies] depend almost entirely on the character and adequacy of the road net. [Argues the obverse for professional armies which have inherently greater mobility.]Let me introduce Winfield Scott into this picture. As if modeling the Mexican War, Scott asked for an army of 42,000 professionals to put down the rebellion, with an equal number of volunteers. Scott envisioned a Patton-like war of professionals augmented by primitive auxiliaries. Lincoln obliged in this but was overwhelmed by a larger response from the states, thereby plunging operational necessity into Patton country: adequacy of the road net, forces of a size only usable in Europe.

The density of improved roads and railroads is much greater in western Europe than in any other portion of the earth. As compared with our highly developed northeastern [USA] area the ratio stands as three to one in favor of Europe.

To maintain the forces employed in western Europe [in WWI] the roads in the zone of the armies were used to their maximum.

Since, then, Europe saw the maximum density of forces capable of being supplied it is evident that since in all other parts of the world conditions are worse, smaller forces will have to be used.

Our General Mobilization Plan [in 1932] contemplates forces of a size only usable in Europe.

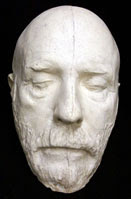

Our old friend Col. John M. Palmer saw Scott as the villain and Lincoln as the accessory: "President Lincoln accepted the official [Scott] proposal and carried it into effect at once. We should not blame him for this error in judgement," he adds helpfully. (This may have been one more nail in the coffin of Scott's influence, IMHO.)

As a "Nation in Arms" gathers in "pools" at its railheads (per Christopher Gabel), Scott's operational concepts are upended; Patton's barely mobile mass armies emerge to crawl over such landscape as is not near rail centers; and McClellan's prescient water- and railcentric plans of 1861 become the mass army consolation prize superseding the irretrievable Scott/Patton professional solution to winning the war.

We have here also the possible emergence of a new meme: that the concentration of volunteer formations into jumbo-sized Civil War armies exceeded their utility by binding their mobility. More on this to come.